There’s a psychological reason why most of the news we see is negative, and unfortunately that bias can have unpleasant repercussions for even the most conscientious mining companies.

Before considering the behavioural science, let me share a story about how one mining company fell victim to this tendency. I won’t go into specifics – no places and names – as I don’t want to embarrass anybody.

Sometime ago an NGO paid a visit to a host community without the mining company's knowledge to see how the company was treating the community. Broadly speaking, the company had made a good effort, raising the local living standards by providing essential infrastructure and jobs in the mine.

The host mining town had expanded because of the economic opportunities the mine provided.

Despite its best intentions and a well conceived engagement plan, the company overlooked a small, outlying group of homes that subsequently sustained damage from mining activity. And the NGO homed in precisely on these individuals.

News coverage isn't always ‘fair’

The NGO used this situation to generate publicity for themselves by ‘exposing’ the mining company’s ‘negligence’ leaving the latter with an undeserved PR disaster to manage. In their publicity campaign, the NGO made little mention of the good work that was being done in the community.

Nor did they point out that the mining company was already working on solutions to help the impacted individuals.

Before going any further, I want to emphasise that every NGO I’ve worked with are, to a person, made up of sincere, passionate individuals committed to doing good in the world – people who would never resort to performative outrage and faux demonisation.

Back to the story. The NGO probably understood that a good news story about a mining company improving local living standards would get little attention with the big media outlets. As the old newsroom saying goes “if it bleeds, it leads”.

An article from Vox found that not only is most news coverage negative, but it is getting worse. I believe similar claims have been made about social media.

And you can see from a purely pragmatic perspective why media channels do this.

An academic article published in Nature Human Behaviour (a journal about online news) found that for a headline under 15 words, the presence of a single negative word increased click-through rates by 2.3% while positive headlines are significantly less likely to be clicked on.

Why bad news thrives

And this brings us to the psychology of why negativity works. The human brain is hardwired to prioritse potential threats over rewards, a feature known as the negativity bias.

Our brains prioritise bad news because, evolutionarily, ignoring danger (e.g. predators, disease, social exclusion) could mean death.

We also tend to remember negative information more vividly and for longer. Again, this aids survival – remembering what caused pain or danger helps us avoid it in the future.

Bad news stories can spread even faster if there is a strong human angle and some novelty is thrown in for good measure.

Fortunately, most negative events in our lives are not life threatening. But that bias in our brains is hardwired into us and is widely exploited by the mass media.

Limits of stakeholder maps

It is quite difficult even for a responsible mining company not to fall victim to this kind of reporting.

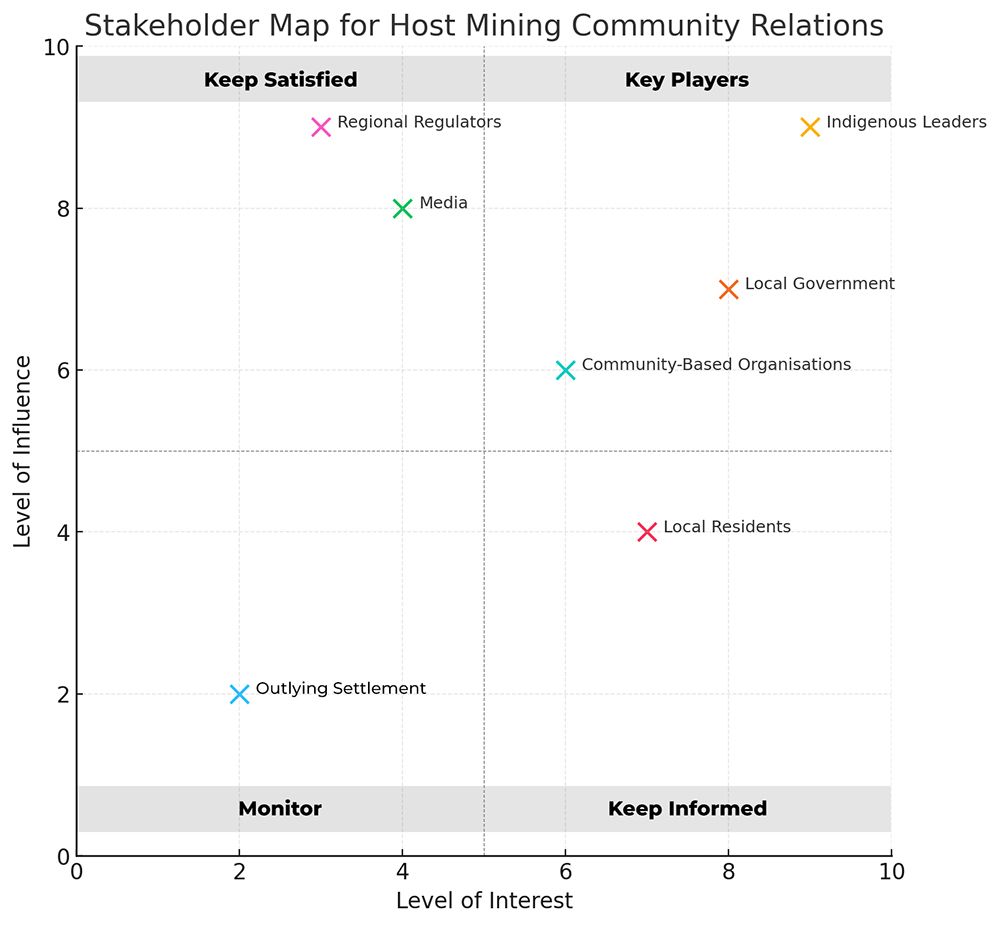

When planning host community relations, most mining companies draw up a stakeholder map to identify, categorize, and prioritize the individuals, groups, and organizations that may affect or be affected by their operations.

The stakeholder map offers a visual representation of the company’s immediate ‘universe of concern’– a framework for developing an engagement plan that supports conscientous, constructive community relations.

The challenge is that this universe is conceptual and incomplete. External actors – unmapped and often unpredictable – can intrude and reshape the stakeholder landscape in unexpected ways. For example, an obscure NGO seeking quick publicity by targeting a small number of homes that have been unexpectedly impacted by a small change in mining activity.

There is no easy answer to what is a tricky twofold problem: mining companies cannot possibly track or predict everything that might affect their universe of concern, and the news media is predisposed to negative stories.

Constant vigilance

When it comes to community relations, the uncertainties and imperfections of the world reinforce the importance of good fundamentals.

A stakeholder map is a living document and should be reassessed at least every three months – particularly if the mine is being enlarged, new machinery is being installed, there are changes in vehicle traffic or new infrastructure is being laid. More generally, it is vitally important to regularly talk with the community so potential issues are identified and addressed as quickly as possible.

Nothing is guaranteed – but being vigilant and responsive will go a long way towards preventing a responsible mining company from falling victim to a bad news story.